Local hero Elsy Borders exposed the corruption behind the 1930s housing boom.

In March 1934, Jim and Elsy Borders arranged a mortgage of £693 and moved into their home on the newly-built Coney Hall estate. Within four years Elsy would unite the residents of Coney Hall, galvanise 3,000 home-owners to go on mortgage strike and inspire a change in the law.

The Coney Hall estate was built during the 1930s housing boom, when land outside the cities was cheap and plentiful. There was an increase in low-cost, new-build homes, and low interest rates were fuelling a previously unthinkable

rise in home ownership.

Elsy Borders moved into her new home on Kingsway in 1934, with husband Jim (a London cabbie) and their three-year-old daughter Pamela. “The Coney Hall Estate is much more than a mere building estate,” claimed the brochure from Morrell’s Ltd, the builders, “for it is a great enterprise both in its conception and in its planning.”

Like most people in the 1930s, Jim and Elsy turned to a building society to secure

their mortgage. They made a substantial down payment of £37 in cash to the Bradford Third Equitable Building Society and agreed a mortgage for £693.

Building societies worked very differently then. With few local offices, they relied on local networks of solicitors, accountants, estate agents and bank managers to survey properties, collect deposits and introduce new business. This not only reduced the cost of expansion for building societies, it also brought captive business based on recommendations and good will.

But that isn’t the only difference in the way building societies worked – there was also the ‘builder’s pool’. This was essentially a cash deposit from the builder, against which the building society would lend an additional amount to the house-buyer. It meant, for example, that a builder would be happy to lend £15 to the buyer of one of their houses via the building society, if it enabled them to sell the house, release capital and guarantee a quick profit.

This close relationship between building societies and builders presented financial and ethical problems. But during the boom years these were largely ignored, perhaps because as the builder’s pool became commonplace, it meant thousands of low-paid workers could buy a new home with only a small deposit. However, while this was true, the builder’s pool also unwittingly funded the rise of the ‘jerry builder’: the type of builder who built houses quickly, cheaply – and sometimes badly.

When Jim and Elsy arranged their mortgage with the Bradford, the building society claimed they’d surveyed the Kingsway property and were happy to arrange the mortgage based on the survey results. But when the Borders moved in to Coney Hall they found cracked walls, peeling wallpaper and sagging ceilings. In reality, the Bradford Third Equitable Building Society was happy to agree to the mortgage because they were part of a builder’s pool with Morrell’s Ltd, the builders.

Jim and Elsy got in touch with the building society about the problems, but nothing was done. The problems only continued, and not just with their house; others in Coney Hall were facing similar problems too. At the time, mortgage payments were collected door-to-door, much like the weekly rent. But in 1937, seeing no other option, Jim and Elsy began withholding mortgage payments until a solution was found. A blaze of local publicity inspired up to 500 other unhappy residents of Coney Hall to join them.

After three months, the Bradford Third Equitable Building Society took the Borders to court for non-payment, but Elsy hit back: she counter-claimed for a refund of the instalments she had already made, plus a massive £500 for repairs. The Bradford, she argued, had wilfully and fraudulently misled her.

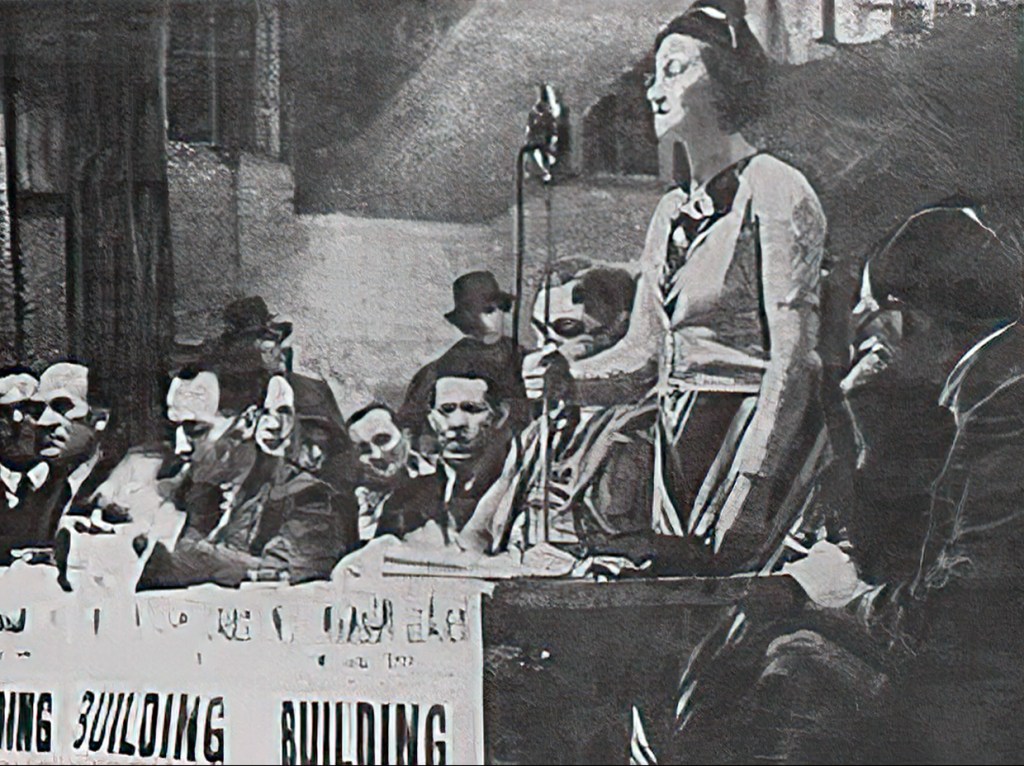

The case began on 13th January 1938, and the court was packed. The attention of the nation was focussed on the plight in which hundreds of thousands of house buyers had also found themselves: with long mortgages and poorly-built properties.

Unable to afford a lawyer, Elsy had spent several months reading law in the London School of Economics and, to the delight of the national press, handled the case herself. She was quick-witted and eloquent, showing such strength the press dubbed her ‘the modern Portia’. She quickly became a hero to thousands nationwide.

It was only when the matter reached the courts that it was revealed that the Bradford had relied partly on collateral security when they made the loan to Jim and Elsy. Morrell’s Ltd were shown to have advertised as “the only builders in Great Britain who can offer by special arrangement with a leading building society a 95% mortgage over a period of 24 years at 5% interest”.

The Borders’ crusade against the building societies gathered momentum with another packed meeting on the Coney Hall estate. Jim Borders spoke to what was then named the ‘Coney Hall and District Residents Association’. He warned the residents that their combined legal struggle might last as long as five years, involving as many as 40 building societies.

For 18 days the legal battle was fought in the Chancery Court. Elsy won the first case, but the Bradford didn’t stop there. They took it to the High Court, and later the House of Lords. Although the final ruling went against the Borders, by then their case had exposed the abuses of the building society system.

“The whole freewheeling apparatus of the boom, the ramshackle financial machine which powered the productivity and profit of it, appeared to be in danger,” wrote journalist Claud Cockburn in The Times.

As the war started the Borders’ case finally dropped out of the newspapers. Sadly the Borders lost their home as a result of the Bradford’s aggressive action. But, their campaign, and the struggles of rental tenants nationwide, shook the very foundations of the political and economic basis of housing policy in Britain. Issues raised by Jim and Elsy, and the thousands who joined them in the mortgage strike, set a precedent, instigated change and led to the passing of the Building Societies Act of 1939.

On Saturday 12 April 2025, a blue plaque was finally unveiled for Elsy at her former home. CHVRA member, Stella Etheridge and local councillor Alexa Michael spoke both about Elsy’s inspirational story and the effort it’s taken to get the plaque authorised in the face of red tape. But, almost two decades of perseverance paid off, and we’re proud to have a local tribute to a remarkable woman.

More information

- Foreign News: After Elsy – Time Magazine, JULY 31, 1939

- A House Called Insanity – BBC Radio 4: “The remarkable true story of Elsy Borders who challenged malpractices in the building industry by refusing to pay her mortgage and then by conducting her own defence in court.”

- British Pathé news clip – contemporary news footage

- An academic look at pre-war housing by Alan Crisp – this is a paper which discusses the building boom in detail, including the builders’ pool.